The Nicest House in the Village

Lorraine Kupitz

My mother, Fania Feldman, was born in a small village near Buczacz, in what was then southeastern Poland. Before the war, her father built a two-family home with money sent from his father in the United States. My mother often said it was the nicest house in the area — so nice, in fact, that when the Nazis arrived, they used it as their headquarters.

She survived the war by passing as a Christian and hiding in the woods. She spoke fluent Ukrainian, had blonde braids, and didn’t look Jewish. Her mother died of illness before the war, and her father — my grandfather — was deported to Belzec. My mother never went back to that village. She said the Ukrainian neighbors may have once been kind, but she knew what had happened to the Jews there and couldn’t face returning.

The house — that beautiful home my family built with hard-earned money from America — was never returned. It became a symbol of everything that was taken from us.

My father was from Krasnobród and later sent to the Brailov ghetto. His mother, two sisters, and brother were all murdered — shot and buried in a mass grave. His home and land were lost too, like so many others.

My parents eventually met in night school in New York, learning English. My father worked hard to save for a proper wedding, and they honeymooned in Lakewood, New Jersey. Years later, they shared their stories through the Shoah Foundation — my father with sharp detail and passion, my mother with calm resilience.

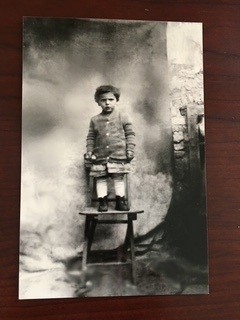

I still have just one photo of my grandparents. Much of the documentation my father left behind is in other languages, and I haven’t yet been able to fully go through it. But I carry their stories with me, and I remember the house — not just for its walls and roof, but for what it meant to our family.

It was more than property. It was a piece of our identity, our history, and our hopes for the future.